Rumi’s Second Most Well-known Work

After the Mesnevi, Rumi’s Divan-i Kebir (also known as Divan-i Shems-I Tebriz) is Rumi’s second most well-known work. Divan-i Kebir means “big notebook, divan being the name given to the notebook in which writers collect their poems. Rumi’s reputation among so many audiences as a the greatest mystic love poet of all time is thanks in part to the work found in his divan.

The Origins of Rumi’s Divan

Rumi began reciting the poems for his Dîvân after he met the Sufi mystic, Shams of Tabriz. We do not know of any one poem which Rumi actually wrote down. He recited his poems extemporaneously, responding to various questions and events or reflecting on his own mystical experiences. His words were written down by scribes known as Kâtib-i Esrar (Secretaries of Secrets). Unfortunately, Rumi’s Dîvân was not compiled during his lifetime. However, in the next century, a number of compilations of the notes of these scribes were created.

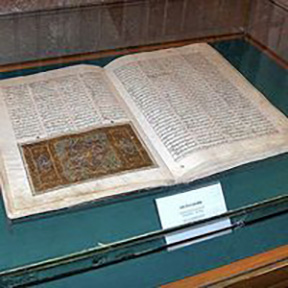

The Osman al Mavlavi Compilation

This compilation is currently housed in the Mevlânâ Museum in Konya, Turkey as numbers 68 and 69. According to Abu Bekir al Mavlavi, the person who made the cover and who most likely wrote the introduction, It was compiled by Hasan ibn-i Osman between July 2, 1367 and October 13, 1368. It is in two large volumes, measuring 17 inches tall and 12½ inches wide, containing a total of 326 pages. The work is in Farsi, the language of poetry of Rumi’s time, with some words scattered throughout in Arabic, Turkish, and even Greek. The total number of individual verses exceeds 44,000, and they are formed into rubaiyat, ghazals, terci-bends and murabbes.

From Medieval Farsi into Turkish into English

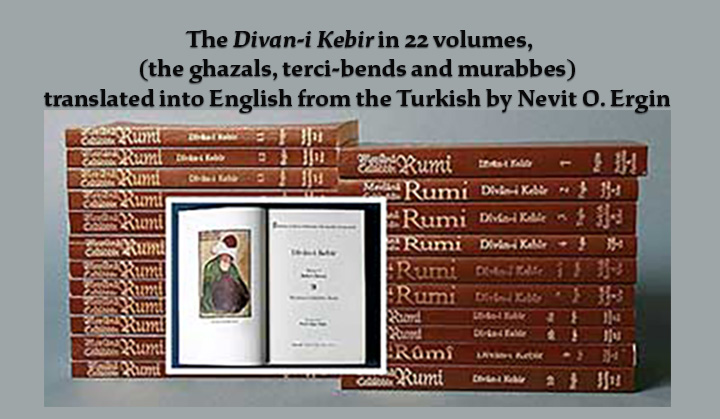

This particular compilation was first translated from Farsi into Turkish by the Turkish scholar Abdülbakî Gölpinarli, and Golpinarli’s Turkish translations were the source Ergin first used to translate the Divan-i Kebir into English.

More on Golpinarli’s Translations

Golpinarli published the first volume of his seven volume Dîvân-i Kebîr Mevlânâ Celâleddîn in 1957 and the final one in 1974. For his Dîvân-i Kebîr Mevlânâ Celâleddîn, Gölpinarli also referenced The Dîvân registered at the Library of the University of Istanbul, No. 334, which was compiled in the 15th century; the Dîvân owned by Gölpinarli himself, prepared in 1691 in Baghdad; and the eight volumes of the Kulliyât-e shams yâdîwân-é kebîr –e mawlânâ jalâluddîn prepared by Persian scholar Badî’uzzamân Forûzânfar (1904-1979) which were completed in 1965. However, he considered the Osman compilation his most reliable course.

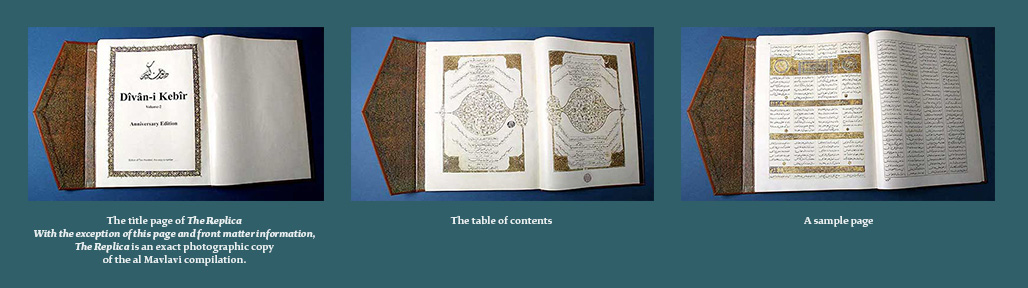

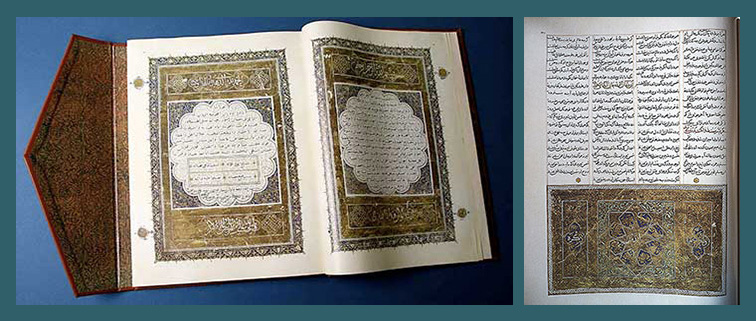

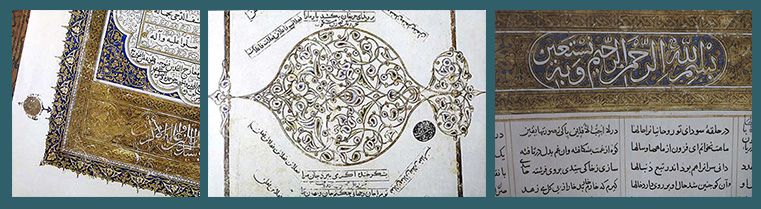

The Replica of the Divan-i Kebir

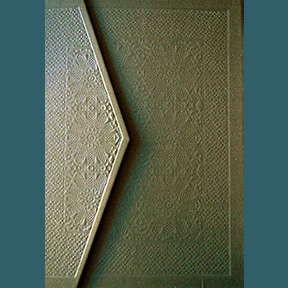

Over the years of traveling between the United States and Turkey, Ergin became good friends with the Director of the Mevlânâ Museum in Konya, Erdoğan Erol. Thanks to Erol’s support, the museum gave him permission to photograph some of the artwork of the Dîvân-i Kebîr numbers 68 and 69, and in 1993, replications of those photos were printed in the first volume of Ergin’s translations of the Dîvân’s ghazals. Then, in 2006, the Turkish Ministry of Culture and the Mevlânâ Museum gave Ergin permission to commission the production of a microfiche of the entire hand-written, two-volume set of that Dîvân; to take color photographs of all of its artwork; and, most important, to reproduce one thousand copies of the set. We refer to this set as the Replica. Thanks to the financial backing of Edmond Gorginian, the publication was made a reality in 2007 through Ergin’s publishing company, Echo Publications, and Ergin’s non-profit, the Society for Understanding Mevlana. Some of the copies have a brown leather cover. However, the majority of the copies have a green cloth cover. Both covers feature the same embossed design as the original compilation. The green cloth cover is featured below.

Accessibility for All

Ergin’s desire was to make it possible for more people to read the Dîvân in its original, hand-written Farsi and for more people to be able to translate from the original Farsi directly into English. He set out to get the Replica placed in libraries and universities across the United States and Europe and to make it available to purchase on the internet. And, of course, once Ergin had the Replica in his hands, thanks to the help of those who could read the original text, he was able to confirm his own translations. Thanks to the help of Shahzad Mazhar who reads medieval Farsi and who loves Rumi’s poetry, we were able to confirm Ergin’s translations as well.

More Examples of the Artwork in the Osman al Mavlavi Compilation

How to get the Pdf copy of Divan Kabir?

Someone messaged me a couple of years ago and said a pdf is available. Look at: https://archive.org/details/Divan-iKebir. That might not be the only source. If memory serves, there was a university that had it. Try google. And, best wishes for finding it…!

Where is the original text? Was Rumi writing in Persian or Welsh? Or does it not matter?

Rumi’s original text is in Farsi, with a little Arabic and Greek mixed in. It is my understanding that Rumi lived in Anatolia, in particular in Konya (in present-day Turkey) the years of his life when he recited the poetry of the Divan-i Kebir, and Farsi was the language of poetry at that time.